Understanding Optimisers Through Hessians

- Jack Norrie

- Machine learning , Deep learning

- 25 May, 2025

Introduction

During my recent autodiff library project I got the opportunity to implement common optimizers from scratch. Furthermore, while investigating the vanishing gradient problem I benefited greatly from diving deeper into concepts that I had previously accepted based on intuitive arguments alone. To further this pursuit of a deeper understanding of deep learning fundamentals, I decided to question my grasp of optimisers.

In the past, I have had momentum explained to me as a way to “have the optimisation more accurately simulate a ball rolling down a hill.” Indeed, adding momentum does make the dynamics analogous to applying (semi-implicit) Euler’s method to a ball rolling down a hill. However, this begs the question: why should this be strived for? What makes the physics of a rolling ball inherently superior for optimisation?

Similarly, I have always had Adam explained to me as a way to “give additional priority to infrequent coordinate updates.” I have never found this motivation very convincing, this sounds like a recipe for instability and overfitting when there are anomalous data points in the training data. I can think of just as many cases where this approach would have a deleterious effect on convergence.

Surely, there is something deeper going on that better explains the general efficacy of both of these approaches.

Deriving Gradient Descent

Suppose we have some loss function

Which means that for small step sizes, i.e. such that

Which means that if we want to maximise the reduction in loss, then we want to minimise the quantity:

The above is the inner product between our perturbation and the gradient. It follows from the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality that minimisation of the above quantity is achieved by pointing our perturbation in the opposite direction of the gradient. Therefore, in order to achieve our desired minimisation, while ensuring our first order approximation valid, we set our perturbation to:

This is the basis for gradient descent, which can be seen as an iterative loss function reduction procedure, which is defined as follows:

Convergence of Gradient Descent

Suppose our current parameter value

We now note that since we are expanding about a local minimum, it follows that

which gives a second order approximation for the gradient of

Since the hessian is symmetric and real valued, it follows from the spectral theorem that there exists some orthonormal basis

Where

We can now revisit our expression for gradient descent with the above expansions in mind.

Which can be understood as a shrinkage of the eigen-components of our perturbation by a factor of

Therefore, it follows that so long as we choose a

Then we will get linear convergence of our perturbation to the zero vector, which is equivalent to linear convergence of our parameter to the local minimum. Importantly, each of the eigen-componenents converge to zero independently, and at different rates for a given

Additionally, we notice that

Importantly, for nonzero

Immediately, this tells us we achieve convergence if and only if

The Steep Valley Problem (ill-conditioning)

Our previous equations present a rather glaring problem, if the eigenvalues of our hessian are separated by orders of magnitude, then a valid choice of

Therefore, given that convergence requires all eigen-componenets to converge, it follows that the rate of convergence for our whole procedure is given by

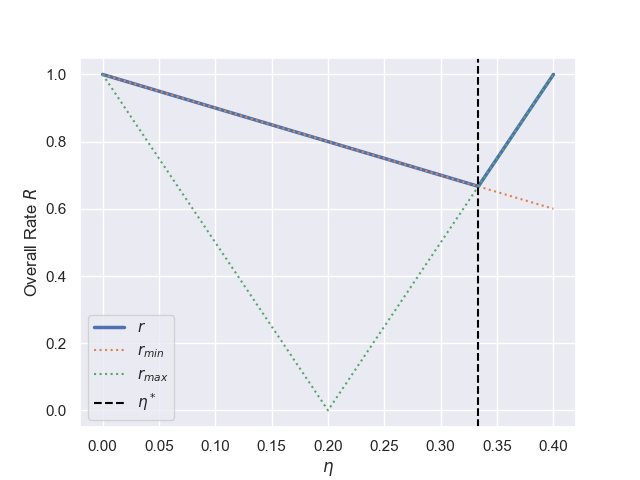

To find the optimal value of

To find this intersection point we observe that it will occur for

The associated value of

Where we have identified the conditioning number

As a concrete example, consider

We notice that if we have a very large conditioning number, the associated overall rate of convergence will be very slow, i.e.

Momentum

With the context of the ill-conditioning problem setup, we are now ready to discuss momentum. Momentum modifies our iterative process by having our gradients directly update a momentum term, rather than the parameters directly. In this sense the gradients now act much more like an acceleration, i.e. something that changes velocity, rather than an instantaneous velocity. Furthermore, we introduce a

A common variant of momentum is Nesterov momentum, this changes the way in which the momentum is calculated as follows:

The key difference is that we evaluate the gradient where the momentum will take us. This makes sense if the size of the momentum term is much larger than the gradient itself. In such circumstances the naive approach leads to gradient evaluations that are irrelevant relative to where the parameter will end up after the update. It makes much more sense for the gradient to act as a small correction term which is applied after momentum moves the parameter.

Lets now study some consequences of the above modification, relative to our ill-conditioned optimisation problem. First lets consider our small eigenvalue component. Given that this component is being updated on an axis of low curvature relative to the update length-scale set by the large eigenvalue component, it follows that the updates at each step are roughly constant, i.e.

We can now use this in combination with our definition of momentum to see that

Which means that a value

From a physics perspective we could compare

to a drag/friction term, in which case the above calculation would be analogous to a terminal velocity calculation.

We can now apply a similar sort of analysis to our maximum eigenvalue component. We notice that for an ill-conditioned problem we have

Therefore, momentum has a small damping effect on oscillations. Reading too deeply into the above result should be cautioned against, since the fact that oscillations are being damped invalidates the assumption that we can approximate the gradient as an oscillating constant, i.e. the gradient will change as we go down the steep valley. Again, this acts to artificially reduce

Adaptive Learning Rate

Motivation

Our previous analyses have been predicated on the assumption that we have set

Nonetheless, lets say we did want to increase the set of minima that we are capable of converging to. Ideally we want to do this without decreasing

Ideally, we would be able to come up with some procedure for estimating

This does not achieve the same linear convergence guarantees as before, and would lead to “oscillation” about the true local minimum, i.e. not truly converge to the local minimum. However, assuming our estimation procedure was effective, it would let us get within a

AdaGrad

One of the first approaches to attempt to tackle the above was Adaptive Gradients (AdaGrad). It simply estimated the scale parameter using the square root of the cumulative sum of gradients squared. Additionally, since we do not know the local minimum’s eigenvectors, we cannot scale across these specific directions. Instead, we simply scale across the coordinates of whatever arbitrary coordinate system our parameters are defined in, which has empirically been shown to work well. The full update rule is as follows:

This was a good first approach, but it does not adapt well to the scenario of our local minimum changing, potentially due to overshooting, since now a previously large component might be very small and need special attention. Furthermore, although the cumulative scale overcomes the “oscillation issue” demonstrated in the motivation for this section, it is too aggresive and leads to training hatling.

RMSProp

Root Mean Square Propagation (RMSProp) builds on AdaGrad by looking at an exponentially weighted estimate of the root mean square gradients. This fixes the issue regarding training halting. The full update rule is given below:

Adam

Adam (Adaptive moments) was introduced in the paper “Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization”. Indeed, its motivation was to stabilise training for stochastic error functions, e.g. those resulting from mini-batch gradient descent and dropout regularisation. The focus of the paper was on robust estimation of the first and second order moments of the gradients using exponentially weighted averages. This is performed as follows:

Furthermore, a de-biasing step is applied, which is used to de-bias these first and second order moment estimates of the gradients relative to their zero value initialisation.

Notice, that this effect becomes negligible as

Finally, the update rule is given by the following:

A common misconception is that Adam is “RMSProp plus momentum”, this being in spite of the paper stressing that this algorithm is distinct from RMSProp plus momentum, which is a perfectly valid optimiser that can be used within most deep learning frameworks. Importantly the “momentum” term in Adam does not perform accumulation, to see this notice that the “momentum” term for some constant gradient update would equal:

In other words, it would not accumulate. Indeed, the purpose of the “momentum” term is not accumulating consistent gradient updates. Instead, as stated above, the motivation for the Adam paper was to provide a more stable training experience for stochastic error functions. Therefore the role of the “momentum” term in Adam is that of gradient smoothing over a potentially noisy training procedure.

A further nice property of Adam is that it allows us to use Jensen’s inequality to further our analysis. Recall that if

Importantly, this means that

Which means that if our first and second moments are estimated correctly, then our gradient step size is bound from above by

Experiments

To finish this investigation off I decided to run some experiments. I looked at a 2 dimensional quadratic optimisation problem. The associated elliptic paraboloid was centered at

MINIMA = torch.Tensor([0.8, 0.6])

LAMBDA_MIN = 1

LAMBDA_MAX = 100

ETA_OPT = 2 / (LAMBDA_MIN + LAMBDA_MAX)

ETA_MAX = 2 / (LAMBDA_MAX)

def f(p):

H = torch.Tensor([[LAMBDA_MIN, 0], [0, LAMBDA_MAX]])

delta = p - minima

return delta @ H @ delta / 2

def optimiser_experiment(

experiment_name: str,

optimiser: Callable[..., torch.optim.Optimizer],

*args,

**kwargs,

):

p = torch.tensor([0.0, 0.0], requires_grad=True)

opt = optimiser([p], *args, **kwargs)

p_history = [p.detach().clone()]

f_eval = 1

epoch = 0

while f_eval > 1e-6 and epoch < int(1e4) and abs(p[0]) < 5 and abs(p[1]) < 5:

f_eval = f(p)

f_eval.backward()

opt.step()

opt.zero_grad()

p_history.append(p.detach().clone())

epoch += 1

p_history = torch.stack(p_history, axis=0).detach()

if not torch.isnan(f_eval):

print(f"{experiment_name} - {epoch}")

else:

raise RuntimeError("Function evaluation overflowed.")

xs = torch.linspace(min(min(p_history[:, 0]), 0), max(max(p_history[:, 0]), 1), 100)

ys = torch.linspace(min(min(p_history[:, 1]), 0), max(max(p_history[:, 1]), 1), 100)

zs = [[f(torch.Tensor([x, y])) for x in xs] for y in ys]

plt.figure()

plt.title(experiment_name)

plt.contour(xs, ys, zs, levels=50)

plt.scatter(minima[0], minima[1], marker="x")

plt.plot(

p_history[:, 0],

p_history[:, 1],

"r-",

linewidth=0.5,

marker=".",

markersize=4,

)

plt.savefig(f"results/optimisers/{experiment_name}.png")

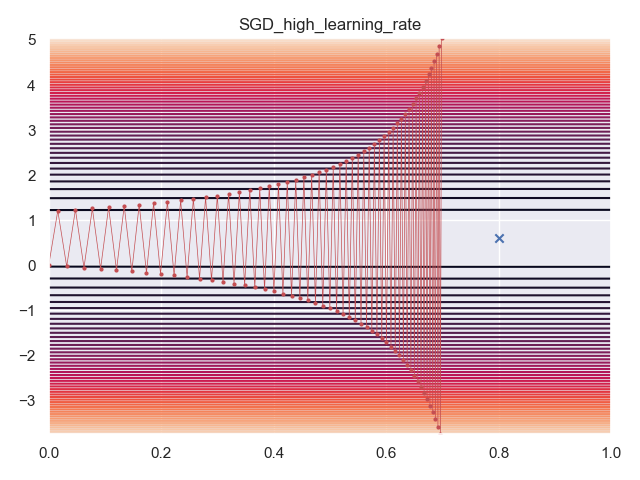

SGD - Learning Rate Too High

First, I used SGD with a learning rate of

SGD

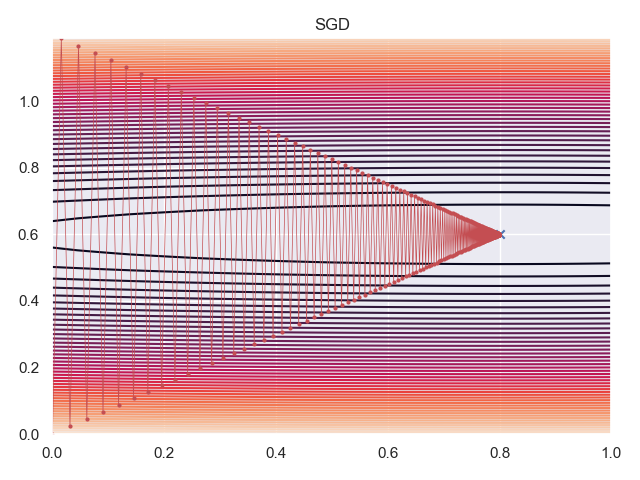

Next, I used SGD with a learning rate of

Momentum

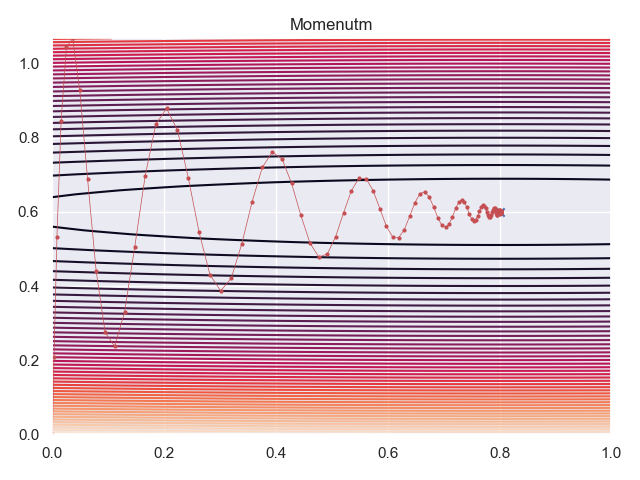

SGD with

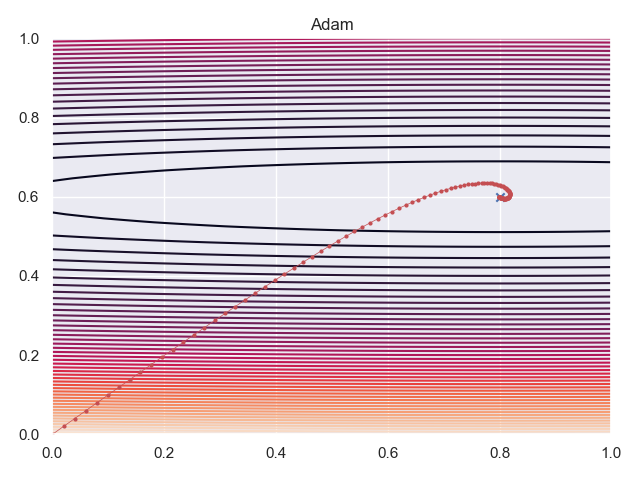

Adam

Adam with a learning rate of

Recommendations

Adam with the defaults of

References

- Bishop CM, Bishop H. Deep learning: Foundations and concepts. Springer Nature; 2023 Nov 1.

- Géron A. Hands-on machine learning with Scikit-Learn, Keras, and TensorFlow: Concepts, tools, and techniques to build intelligent systems. ” O’Reilly Media, Inc.”; 2022 Oct 4.

- Kingma DP, Ba J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980. 2014 Dec 22.